What is a Canonical Approach to the Bible? A Brief(ish) Explanation

Introduction

In my previous blog, I mentioned that for most of my life, I had a inadequate understanding of the Bible. When God provided me the circumstances and instruction to change that, my faith grew by leaps and bounds.

Because of the method I was taught, I gained confidence in my personal Bible study, which increased my closeness to God, understanding Him better, and helped me to live more in line with the faith I claim.

I started learning the inductive method in the New Testament. But when I went back to the Old Testament, I found that I could keep track of my observations (first step of the inductive method), but I was missing something. The stories of the Torah (Genesis – Deuteronomy in our English Bibles) were still confusing to me.

Just like I had learned how to study the type of literature in the New Testament (specifically, the epistles is where I focused most of my personal study), I had to learn how to study the kind of texts that make up narratives of the Old Testament (which are very similar to the texts of the Gospels).

That’s what this blog series is about: reading the literature of Old Testament stories[1]. The introduction will be an explanation of the canonical method, which is the method used to read and learn from the Old Testament narratives. Then, in order to give meaning to the method, the subsequent blogs will be demonstrating that method in various narratives and teachings based on those passages.

So, join me as we dive into the canonical method:

The Bible is Written Text

The Bible we have is a written text. It seems silly to point out such an obvious fact but it’s a foundational point that we must agree upon when we talk about a canonical approach to the Bible.

God has revealed Himself in written language. The Spirit inspired the authors of the canonical (official) books of the Bible—He inspired the words that the authors used, and the way they used those words to communicate themes and ideas through the stories they formed (or the poetry they wrote, or the prophecies they recorded, or the arguments they made). This canon of Bible books is the standard we use to interpret the individual units of Scripture[2].

This interpretive formula acknowledges that we readers are looking at individual books by individual human authors but ultimately there is One Author of one big story. And knowing that this one big story is by One Author helps us understand that we must be looking for the unity (interconnectedness) of the entire Scripture. We do not read individual stories as disconnected from each other but as a part of the whole. And that whole gives us the meaning of the individual pieces. That’s why we say this approach to understanding the Bible is canonical.

That point helps us to circle back around to our agreement on that first fundamental point: Scripture is a written text. One Author inspired humans to write down His revelation by means of human language. If we want to know about God and His plans for the people and the world He created, we must understand who the text of Scripture reveals Him and His plans to be. And if we want to understand what the text shows, we have to understand how the text works to teach us those truths. We understand the truth of Scripture by understanding the words of Scripture.

Historical Narrative

The upcoming blog series will be (mostly) based in the Pentateuch[3], and the type of literature that we’ll be looking at here is called “historical narrative.” According to John Sailhamer, “Historical narrative is the re-representation of past events for the purpose of instruction.”[4] Historical narratives communicate truths through stories, not through telling (e.g. Paul’s epistles tell truths to readers, but the Gospels, like the Pentateuch, use narratives to show truths). The authors of the narratives show us theology, they don’t write out something akin to the Westminster Confession.

So, back to historical narratives. These stories of the Pentateuch are historical in the sense that the writer details past events. For example, the creation of the heavens and earth, of the land, of animals, and of humanity are events that happened in history. We can read about those events in Genesis 1 and 2.

But the “re-representation of past events” that the author composed is a historical narrative, meaning that the author crafted a story (narrative) about those past events in order to instruct readers about the purpose and meaning of those events.

Using creation again as an example, the author shows the story of God’s work “in the beginning” not just to tell us facts about Creation, but to weave a story for the purpose of teaching the reader things about God, and about the land He prepared, and about the people He made to inhabit that land.

And in this first[5] narrative, in the written re-representation of Creation, the author prepares the reader for the whole story of the Pentateuch by showing God’s purpose for His creation. The writer also introduces and establishes patterns and central themes in the Creation passages that can be traced through the entirety of Scripture.[6]

The Purpose of Patterns

These patterns, established and repeated throughout the Pentateuch, are descriptive of a literary device called narrative typology. Narrative typology is a system in which “earlier events foreshadow and anticipate later events. Later events are written to remind the reader of past narratives…By means of [narrative typology] the author develops central themes and continually draws them to the reader’s attention.”[7]

Practically, the writer “does” narrative typology by repeating words, phrases, and concepts within and between distinct narratives[8]. We call these repetitions patterns, parallels, recasting, and recursions.

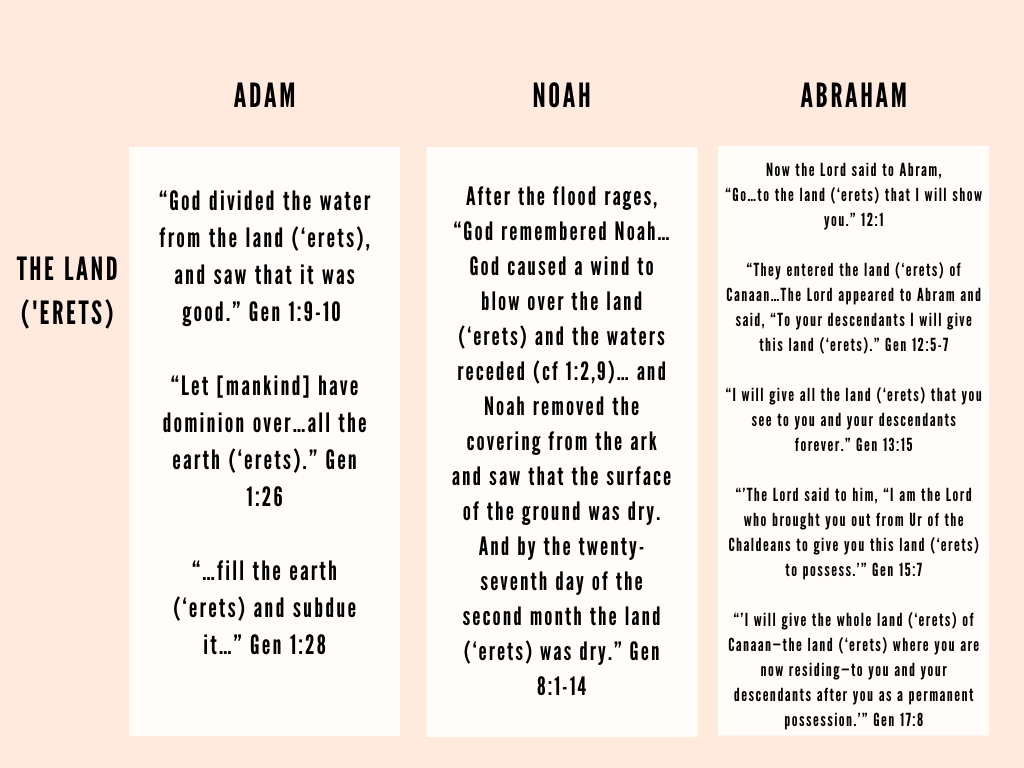

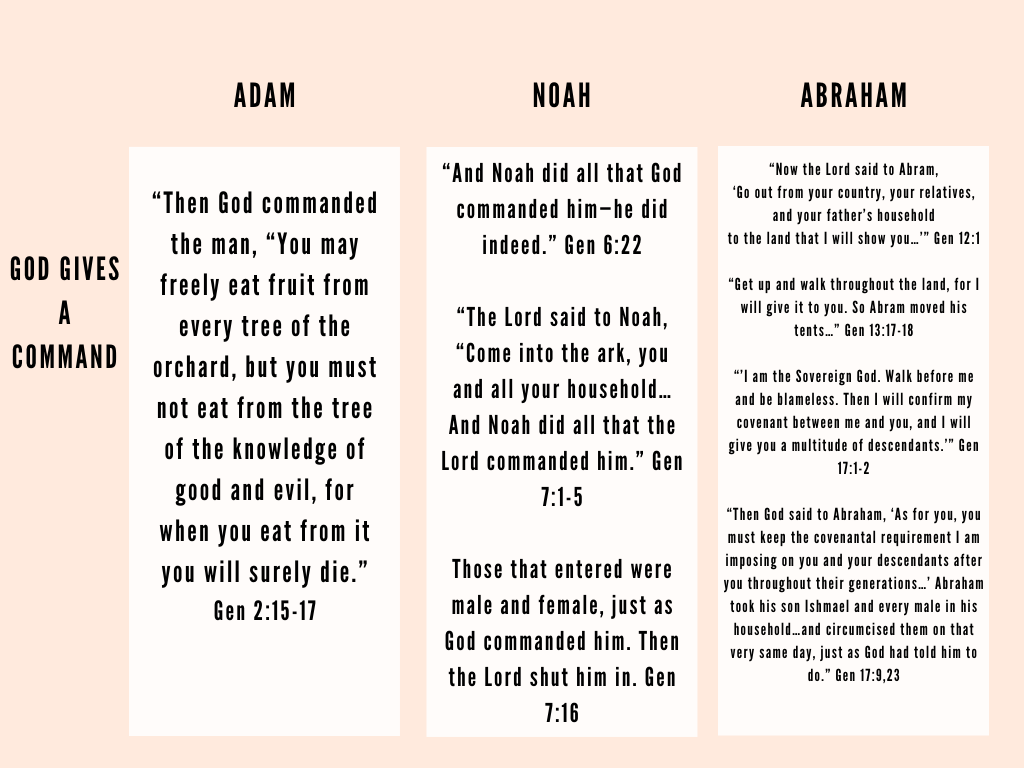

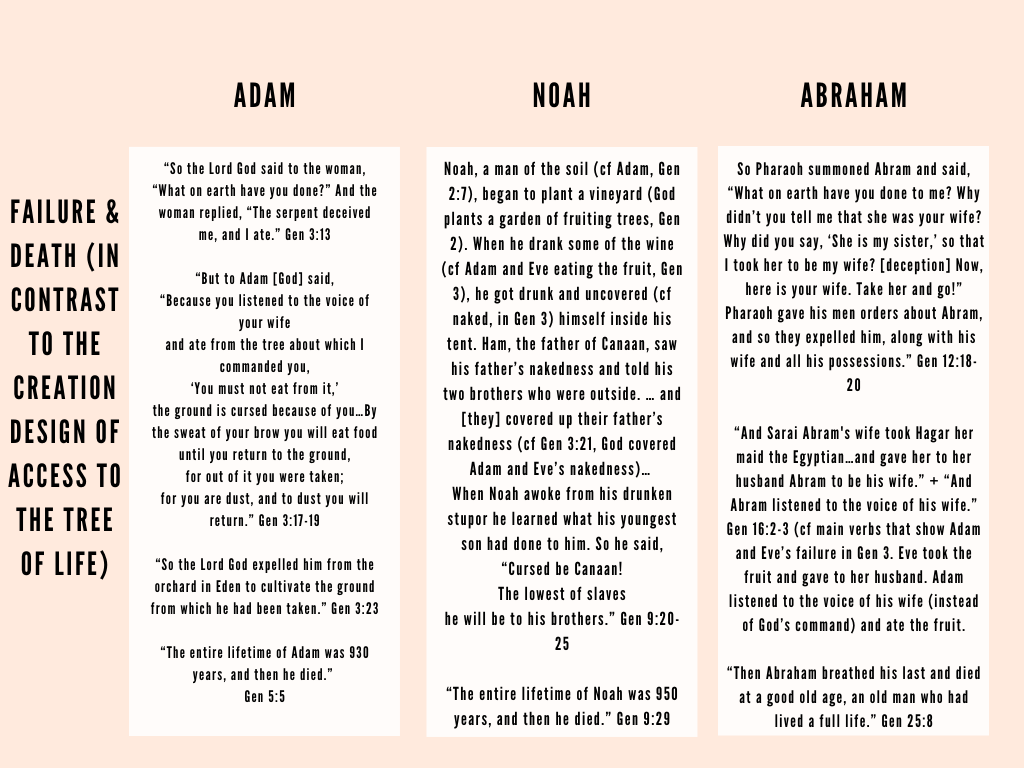

The author writes Abraham as looking and sounding and behaving like Adam. That is to say, Adam is recast as Abraham. Or we could say it this way: Abraham is patterned after Adam.

Adam is recast in Noah; Noah is patterned after Adam. Abraham is recast as Isaac; Isaac is patterned after Abraham.

This recasting of characters, creating patterns and parallels, is accomplished via repeating the same words and ideas in each of the narratives.

A brief example from my own observations of the recasting and parallels of Old Testament individuals[9]:

Why does the author repeatedly recast these men[10]? To connect those persons and their situations within the book that he wrote. Linking people and situations enables readers to see the central themes being carried down the line of narratives; themes that are crafted at the beginning (literally) and propagated throughout the entire book.

Like flashing lights, repeated words and phrases within and between narratives are signals that say, “Doesn’t this sound familiar? Notice how the same thing keeps happening? I’m linking these stories to tell you something important!” So, the repetitions are the lamps that illuminate the narrative threads that are weaving one, cohesive story.[11]

For the patterns laid out in the table above, we can draw one basic but very important truth: God intends to bless His people. Even though there is failure on the part of mankind, God continues to raise up a people for Himself. Adam failed, was exiled from the good land that was full of food (Gen 3), and eventually died (Gen 3; Gen 5:5). Abraham, a descendent of Adam, experiences failure (though he also experiences major success), experiences an expulsion from the land of food (Gen 12), and eventually dies. Isaac (Abraham’s son) and Jacob (Isaac’s son) also fail at points, and they too die.

Even Joseph (Jacob/Israel’s son), who epitomizes what God’s man should be like,[12] eventually dies[13]. Ultimately, God’s commitment to the blessing meant sending His own Son so that through Him, a multitude of sons and daughters would be added to Abraham’s family by faith and inherit the blessing[14].

Our Goal

Our goal in this series will be to use the canonical approach; to observe the repetitions and patterns, the narrative typologies, as a way of learning about the central themes of Scripture. This study will be based in the actual text of Scripture, the revelation of God to mankind. Observing the flashing lights of the texts, and considering the truths they illuminate, will help us gain a greater grasp on the one big, unified story of Scripture and what that story reveals about our good and faithful God.

In the next post, we’ll consider how the canonical approach to reading the Bible is practical for everyday Bible readers, not just for scholars or theologians.

Footnotes:

[1] There are a variety of genres in the Old Testament. I will be focused on narratives for this series, not, for example, prophecy or the wisdom literature.

[2] There are units or parts within single books. A single book may be its own unit, but there are often smaller units within. For example, the book of Psalms has 5 parts. However, discerning units within a broader unit is not always readily apparent, especially if we rely on the chapter divisions or subheadings added into texts after they were written. The Torah, or the Pentateuch, is traditionally split into 5 books. However, this 5-book split can be misleading because some units of narrative go beyond the borders of the traditional separation. For example, Exodus 15 through Numbers 10 is one unit, where the Israelites journey to and camp at Mt. Sinai.

[3] Traditionally, the Pentateuch is split into 5 books: Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Within the written text of the Bible, however, these 5 books are always referred to as one book, e.g. The Book of Moses, The Book of the Law. Cf Deut 30:10; Josh 1:8; Mark 12:26; Gal 3:10

[4] John H. Sailhamer, The Pentateuch as Narrative: A Biblical-Theological Commentary, Library of Biblical Interpretation (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan Publishing, 1992), p. 25, emphasis added. This text is an incredible resource for learning about the narrative and literary unity of the Pentateuch. The introduction has in-depth reasoning as to why Sailhamer believes the Pentateuch’s author intentionally connects narratives together, and shows proof after proof within the body of the commentary that the unity (connectedness) exists through observing narrative typology. I will briefly introduce the concept of narrative typology in this blog.

[5] First not only in the chronological sense but first in the sense of primary importance. That’s what leads me to assert that the Creation narratives are normative—a paradigm for what was created then and for all of time.

[6] To reassert this important point: the One who inspires inspired one, unified written revelation through all the authors and all of their written works that comprise the Bible.

[7] Sailhamer, p. 37; We believe Sailhamer because an even more important author has discussed this concept: the inspired apostle Paul talks about the pattern of foreshadowing. Romans 5:14 "Adam is a type of the one who is about to come."

[8] Biblical authors also use grammatical patterns and story placement within units of Scripture to do the work of creating patterns and parallels.

[9] I’ve chosen only 4 words/themes for this table. There are numerous links, too many to discuss in this introduction.

[10] It’s not just men who look like other past or future biblical people. As noted above, Isaac is depicted as Abraham, etc. But Sarah looks like Eve, and she in other ways looks like Pharaoh in Exodus, and even King Saul in 1 Sam 24. Events are also recast as future and past events: the Flood is recast as a new Creation. The Exodus is also recast as a type of new Creation.

The meat of the upcoming blog series will deal with examples of narrative typology and what we can learn from these patterns.

[11] In the Pentateuch, but also throughout the entire biblical story.

[12] Joseph is raised to rulership (theme of dominion from Gen 1).

He leads the family of Israel into the good land and feeds them (God puts His man into the good land full of trees that are good for food, Gen 2), which prevents the people’s death from famine (contrasting Adam and Eve’s expulsion from Garden that included the Tree of Life, Gen 3).

Joseph marries just one woman (Garden marriage, Gen 2), and is blessed with two children (“be fruitful and multiply,” Gen 1).

But even Joseph dies at the end.

[13] Again, see Romans 5:14, “Yet death reigned from Adam until Moses even over those who did not sin in the same way that Adam (who is a type of the coming one) transgressed.”

[14] See Galatians 3 for the telling of this truth; the Pentateuch is showing us this truth in narrative, in story form. Important to Galatians and to the Pentateuch, and not discussed in this introductory blog, is the problem of the law and where righteousness comes from.